They Came Back in Eight Weeks

What happened in Antarctica that made every nation fall in line

The Antarctic Treaty expires in 2041. Fifteen years from now. Three presidential terms. Whoever takes the oath that January inherits whatever has been frozen in place since 1959.

General George S. Patton was killed in December 1945. A low-speed car accident in occupied Germany, a truck pulling out in front of his Cadillac on an empty road. He’d survived the entire war. Then, twelve days before Christmas, a broken neck from a fender-bender.

Patton had been saying things. The wrong enemy. The real threat. The war reframed before the bodies were cold. He wanted to keep going east, and certain people needed him to stop talking.

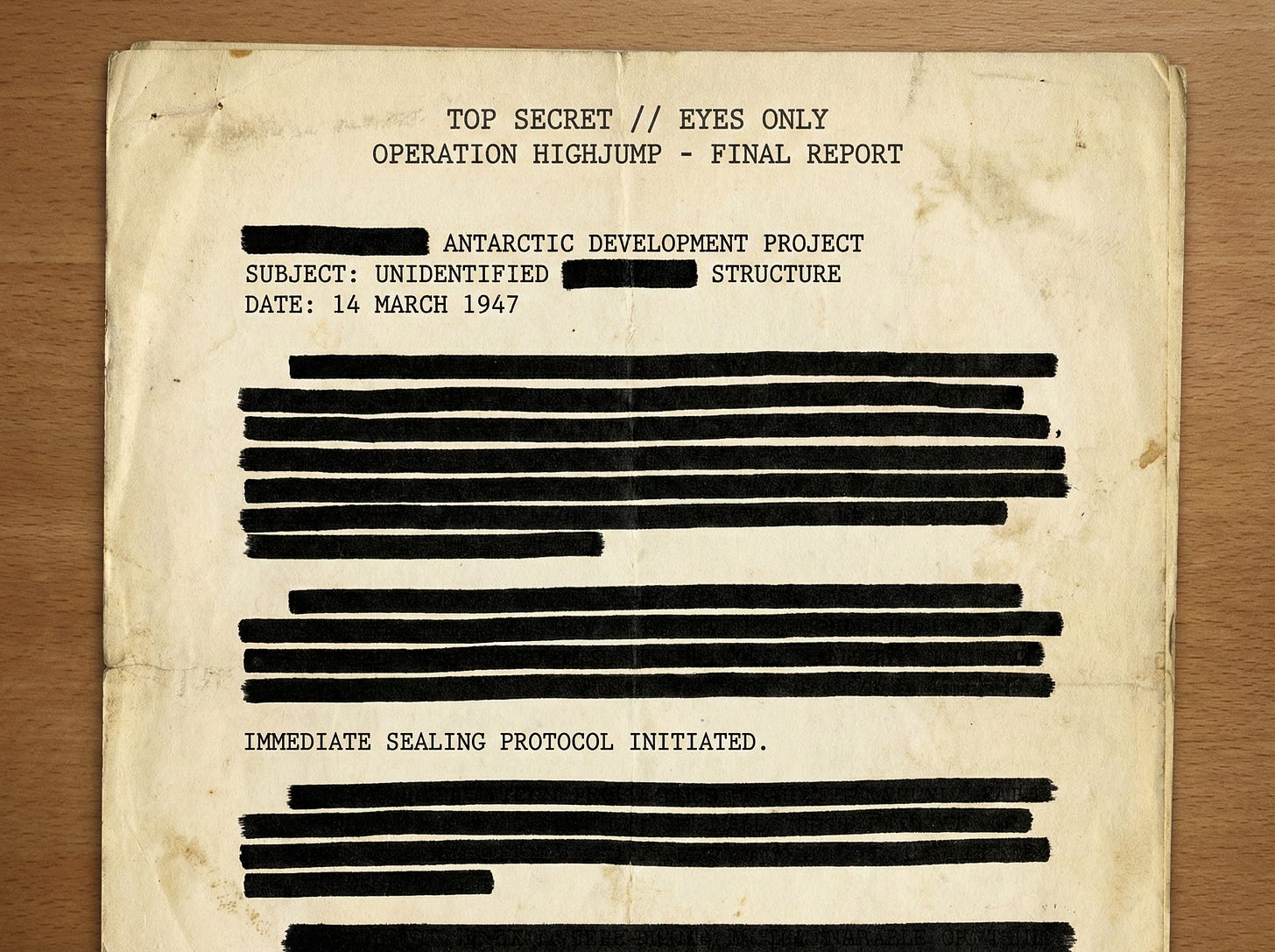

Six weeks after they buried him, the Navy launched Operation High Jump.

The scale was unprecedented. 4,700 men. Thirteen ships including an aircraft carrier. Twenty-three aircraft. The largest Antarctic expedition ever mounted, larger than many naval combat operations. Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal went personally.

You don’t send the Secretary to the bottom of the world to count penguins.

Admiral Richard Byrd was America’s most celebrated polar explorer.

First to fly over both poles. A national hero in the truest sense. Before High Jump departed, he gave an interview to a Chilean newspaper. He said the next war would be fought by aircraft that could fly from pole to pole at incredible speeds. Antarctica, he said, was part of a strategic picture the American public didn’t understand.

The expedition was scheduled for six to eight months. Standard polar protocol. You go in the summer, stay through the long light, do your work, come back before winter locks you in.

They came back in eight weeks.

No explanation. The Navy said the mission objectives had been completed ahead of schedule. Byrd said nothing publicly. But the official record shows that the expedition encountered something they weren’t prepared for.

What happened during those eight weeks has never been fully disclosed. The rumor that persisted through military channels was that Byrd’s forces encountered craft that moved in ways American technology couldn’t explain. Disc-shaped. Fast. Not German, because the German scientists were already working for us. Not Russian, because we knew what the Russians had.

Something else.

Four months later, something came down near Roswell.

Byrd lived. He did a TV interview in 1954 on Longines Chronoscope, sitting in a studio, talking calmly about Antarctica’s untapped riches. Vast mineral wealth. Enough coal to fuel the world for centuries. He spoke openly, confidently, like a man describing a real estate opportunity.

Nobody came for him. He died in his bed in 1957.

Forrestal was different.

He’d been on the ice with Byrd. He’d seen whatever it was that made them leave early. He was one of the first officials to view what was recovered in New Mexico. He didn’t just sign off on the missions. He saw what they brought back. He understood the implications in a way that Byrd, the explorer, never had to.

Byrd saw terrain. Forrestal saw a problem that couldn’t be solved.

1949

By 1949, he was coming apart. The official diagnosis was “nervous exhaustion,” which was the polite term they used back then. He was talking about forces the American public couldn’t comprehend. About infiltration at the highest levels. About an enemy that operated outside the normal categories of nation-states.

They said he was paranoid. They put him in Bethesda Naval Hospital. Sixteenth floor. For his own protection, they said.

The official story is that James Forrestal committed suicide by jumping from his hospital window in the early morning hours of May 22, 1949.

But the details don’t add up.

He was under constant observation. Suicide watch. Yet somehow, in the middle of the night, he gained access to an unsecured window in a room that wasn’t his. The cord from his bathrobe was found tied to a radiator, broken.

Here’s what the Warren Commission-style investigation never explained:

Forrestal didn’t use the cord to hang himself. He tore through it. The bathrobe was ripped. The cord was broken at the knot, not from his weight, but from being pulled apart.

He refused to be found in bed with a stopped heart. Another quiet file closed. He made a mess on purpose, because messes ask questions. They found that transcription of Sophocles on his desk, the chorus from Ajax about the nightingale. A man who couldn’t sing in his cage.

Forrestal turned himself into a question that couldn’t be answered by calling it suicide. And questions, he knew, last longer than the men who ask them.

1959

Twelve years between Operation High Jump and the Antarctic Treaty. Twelve years isn’t bureaucracy. Twelve years is a negotiation that couldn’t be resolved through normal channels.

The Soviet Union had captured German records from the war. Whatever the Reich had been doing at the South Pole, the Soviets knew about it. Stalin claimed territorial rights based on Russian expeditions in the 1800s, a legal argument that would normally be laughed out of any room. Instead, the U.S. Secretary of State resigned. Argentina and France backed the Soviet position. America lost leverage in ways the historical record doesn’t fully explain.

The 1959 Antarctic Treaty wasn’t a victory for anyone. It was a truce.

No military activity. No nuclear testing. No territorial claims enforced. Scientific research only. And every signatory nation agreed to let inspectors from any other signatory nation visit their facilities at any time.

Think about that. At the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the United States agreed to let each other inspect their Antarctic bases without advance notice. The same two powers that couldn’t agree on anything else, that were pointing nuclear missiles at each other’s cities, that were fighting proxy wars on four continents, agreed to total transparency in Antarctica.

Why?

Because both sides had seen what was there. And both sides knew that compared to what was under the ice, their differences with each other didn’t matter.

The treaty has been in force for sixty-five years. Perfect compliance. Zero violations.

Not one. Not from superpowers with thousands of nuclear warheads. Not from rogue states that ignore every other international agreement. Not from corporations that would drill through their grandmother’s grave for oil. Not from nations that have broken every other treaty ever signed.

This one holds.

Every other international agreement has been violated, reinterpreted, withdrawn from, or ignored when convenient. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty has been broken repeatedly. The Geneva Conventions are treated as suggestions. Climate accords collapse. Trade agreements get renegotiated. Borders get redrawn by force.

The Antarctic Treaty holds.

Ask yourself what could make every nation on earth obey the same rule for sixty-five years straight. What could make enemies agree. What could make greed take a back seat to compliance.

The answer isn’t diplomacy.

1982

In 1982, Britain and Argentina went to war over the Falkland Islands.

On paper, it makes no sense. A few rocks in the South Atlantic. No oil reserves known at the time. No strategic value in any conventional military sense. Population of fewer than two thousand people. The British had to send a naval task force eight thousand miles to fight for sheep pastures.

The official explanation is national pride. Argentina’s junta, distracting from collapse. Thatcher, needing a boost in the polls.

But the Falklands are the gateway to the Antarctic Peninsula. Whatever you’re bringing out of Antarctica, or into it, passes through those waters.

After the war, something strange started happening at Marconi, the British defense contractor. Their scientists began dying.

Between 1982 and 1988, twenty-two Marconi employees working on classified electronics projects died under unusual circumstances. Suicides by methods that defied belief. Accidents that didn’t add up. One man tied a rope around his neck and the other end to a tree, then drove his car forward. One drowned in his backyard pond. One walked in front of a truck. One was found in his car with a hose from the exhaust, in a garage he’d never used before.

All ruled natural or self-inflicted. Twenty-two scientists in six years, all working on classified projects, all connected to what the Falklands War had really been about.

The Falklands weren’t about territory. They were about custody. And whatever was recovered from those cold waters, certain people didn’t want it talked about.

The families who understood what was recovered started buying land in Paraguay. Ask yourself why.

There’s a facility at the South Pole called the IceCube Neutrino Observatory. The official description says it’s a passive scientific instrument designed to detect neutrinos, subatomic particles that pass through ordinary matter without interaction.

5,160 sensors are buried a mile deep in the Antarctic ice. The strings of detectors extend down into the darkness, watching for the faint blue flash that happens when a neutrino occasionally strikes an atomic nucleus.

Raytheon operates it. The same defense contractor that builds missile defense systems and directed energy weapons. The same company that runs logistics for multiple Antarctic stations. The same company that employs men who sign security clearances and don’t talk about what they’ve seen.

The power requirements don’t add up. The official South Pole station has declared generator capacity for the personnel who live there and their scientific equipment. IceCube supposedly runs on the same grid. But the facility’s actual power draw exceeds what passive optical sensors should require by orders of magnitude.

Contractors who’ve worked there talk about it. Some of them have gone on record. They describe infrastructure that doesn’t match the official mission profile. Equipment that doesn’t appear in any published inventory. Power consumption that can’t be explained by watching for faint blue flashes.

The pattern is familiar: a classified facility hidden inside an unclassified one. A cover story that explains enough to satisfy the curious but not enough to explain what’s actually happening. And a defense contractor running the show, the same way they’ve run it since High Jump.

The frame that makes sense of Antarctica isn’t aliens landing in silver ships. That’s the story they want you to chase, because it’s easy to ridicule and impossible to prove.

It’s not hollow earth, either. That’s another distraction, another rabbit hole that leads nowhere useful.

The frame that fits the evidence is jurisdiction.

This planet has boundaries that predate the nations on it. Lines that were drawn before humans had maps. The ice marks one of them. Everyone who matters figured this out a long time ago, and they agreed to stay on their side of the fence.

The Antarctic Treaty isn’t really an agreement between nations. It’s compliance with an existing rule. When every power on earth, including powers that have spent the last century trying to destroy each other, agrees to stay behind the same line for sixty-five years, that’s not politics. That’s everyone reading the same sign and deciding to obey it.

Whatever is under the ice, or beyond it, or watching from it, has authority that human governments recognize even if they don’t acknowledge it publicly. The treaty isn’t a decision we made. It’s a condition we accepted.

2016

John Kerry went to Antarctica in November 2016, days after the American election. The official reason was climate research. He was photographed looking at glaciers, talking about ice loss, doing the things that diplomats do when they want to seem concerned about the environment.

But Kerry wasn’t a climate scientist. He was the Secretary of State. And he went to Antarctica during the most sensitive political transition in modern American history, when the Obama administration was scrambling to respond to an outcome they hadn’t expected.

What was so urgent that it couldn’t wait for the new administration?

Kerry talked publicly about the 2041 treaty renewal. He said different countries were beating on the door. Wanting in. That phrase stuck. Wanting in.

China is building bases on the ice. Russia is reasserting territorial claims that the treaty was supposed to freeze. The consensus that held through the Cold War is breaking down. The generation of leaders who understood the original arrangement is dying. Their successors don’t have the same fear, because they never saw what made their predecessors afraid.

The door has been sealed since 1959. Sixty-five years of everyone agreeing to leave it alone.

Someone is going to test the lock. And whoever’s on the other side of it will have something to say about that.

2041

Forrestal saw this coming. He understood that the arrangement wouldn’t hold forever. That the secret was too big for any structure to contain indefinitely. He turned himself into a question because questions last longer than answers. Messes outlast clean files.

Kennedy saw it too. Whatever he learned during his years in intelligence, whatever he discovered when he started digging into the apparatus his own government had built, he decided to break it open. He talked about secrecy being repugnant in a free society. He moved to strip power from the intelligence agencies. He reached out to Khrushchev about sharing space, about ending the Cold War charade that kept both populations in fear.

They killed him in daylight because he wouldn’t die in the dark. The message was clear to anyone who understood it: this is what happens to presidents who try to open doors that are supposed to stay closed.

Those who see too much and talk about it die strangely. Those who see and stay quiet get to live out their years. Byrd talked about riches and opportunities, and they let him do his television interviews. Forrestal talked about forces beyond comprehension, and he went out a window.

The men who made the original deal are dead now. Forrestal, Byrd, the generals who saw what was in those hangars, the scientists who were brought in to study what couldn’t be explained, they’re all gone. Their successors are dying. The men who were briefed in the 1970s and 1980s are in their final years.

The walls between compartments are thinning. Too many people have been read into too many programs. The secret has been kept by a structure, and structures decay. What happens when the last people who understood the full picture are gone?

Fifteen years until the treaty comes up for renewal. Three more presidents from now. Whoever takes that oath inherits the question of what to do when the arrangement expires.

The ice has been patient for a long time. It can wait another fifteen years.

But the people who want what’s underneath it are getting impatient. And the door that’s been sealed since 1959 is starting to rattle.

<3 EKO

The full story of Forrestal, the cage he built, and the man who tried to break it open is told in KENNEDY: SHADOW CLEARANCE.

If you’ve already read it, leave a review. Make some noise.

And if this work matters to you, support it directly.

100% goes to the mission.

The ice is listening.

I love you.

Interesting this rabbit hole you decide to sojourn EKO.

Thankfully my Father lived out his days to 100 before dying peacefully in his bed, he was a double PhD (physics and aeronautical engineering). He began his professional career at Groom Lake in 1952, then went on to work at the Skunk Works for Lockheed and many other places I remember he always was traveling to and working including Wright Patterson AFB, Huntsville Alabama and Wichita.

Truth seeking is an uncomfortable and sometimes fatal endeavor.

Personally, I think there are a great many things we are being distracted with in all forms of communication and narrative forcing. There are things approaching in February 22, 2026 which have not happened in our star system for 12,000 years. Interesting things happened in the timeline of humanity in December 21, 2012 and perhaps these generations living today will see and experience those things foretold for many generations preceding. The Looking Glass converges the timeline while the Yellow Book, or Yellow Cube as it were, tells the story untold.

The coming battle for custody of we know not what…knowledge that is accompanied by a death sentence

Nothing is as it seems