On Sabbath afternoons, when the work stopped and the town grew quiet, Joseph would take his son walking.

They climbed the high hill near their home, the one that rose above Nazareth like a watchman. From the top, you could see everything. Mount Carmel to the northwest, its long ridge running down to the sea. Mount Hermon to the north, its peak white with snow even in summer. The Jordan valley to the east, and beyond it the rocky hills of Moab. To the south, the broad plain of Esdraelon stretching toward Samaria.

Joseph would tell stories as they walked. Elijah on Carmel, confronting the priests of Baal. Gideon in the valley below, routing the Midianites. The battles and prophets and kings who had walked this land before them.

Yeshua listened. Asked questions. Pointed at things Joseph couldn’t explain.

“Why is the snow on Hermon but not here?”

“Because it’s higher. Colder.”

“Why is it colder when it’s closer to the sun?”

Joseph had no answer for that one.

These walks became the rhythm of Yeshua’s childhood. Every Sabbath, weather permitting, father and son climbed the ridge and looked out at the world. Joseph taught him to read the land, to understand distances and directions, to see how the trade routes connected cities he’d never visit.

And sometimes, when the wind died and the light turned copper, they just sat. The sun dropped into the sea and the sky burned out behind it and neither of them said anything.

Nazareth was not a quiet town.

Four miles away, Sepphoris was being rebuilt into a Roman showpiece, and Nazareth existed to feed the construction. Carpenters, stonemasons, laborers. They passed through constantly, along with the caravans that used the crossroads. Greeks and Jews and travelers from lands Yeshua had only heard of.

The family home sat near the village spring, which meant an endless stream of visitors. Women came for water and stayed for gossip. Caravan conductors stopped to rest their animals. Joseph’s workshop drew customers from across the region.

Yeshua watched them all. Listened to their languages. Asked about their cities. By the time he was eight, he could hold conversations in Aramaic, Greek, and passable Hebrew. By ten, the caravan traders knew him by name.

“Your boy asks more questions than a Roman tax collector,” one merchant told Joseph. “But at least his are interesting.”

School began at seven.

The synagogue classroom was simple. Students sat on the floor in a semicircle while the chazan taught from the scrolls. They started with Leviticus, moved through the law and the prophets, memorized by repetition. The chazan would speak a line; the students would repeat it back.

Yeshua was a good student. Diligent. Quick. He’d already mastered Aramaic and Greek before he arrived, which gave him an advantage. But it was his questions that set him apart.

“Rabbi, if the Lord commanded us not to work on the Sabbath, why did he work for six days creating the world? Wasn’t that work?”

“If we’re not supposed to make images of things in heaven or earth, why did Moses put a bronze serpent on a pole?”

“The law says to honor your father and mother. But what if your father tells you to do something you believe is wrong?”

The chazan was a patient man. He’d taught children for thirty years. But this one made him pause mid-sentence and look out the window, as if the answer to whatever the boy had just asked might be out there somewhere, drifting past.

The village parents talked.

They said the boy asked too many questions. They said he confused their children. Their children came home confused by things Yeshua had said, and the parents blamed him for stirring up trouble.

And there were the boys who hated him for it.

Yeshua wouldn’t fight. He was strong enough. He just wouldn’t do it. Older boys pushed him and he stood there. They mocked him and he watched them until they ran out of words. That silence made them wilder.

His friend Jacob solved the problem.

Jacob was the stone mason’s son, a year older, built like a young ox. He’d decided early that Yeshua was worth protecting, and he made it his business to ensure no one touched him. The older boys learned quickly that bothering Yeshua meant dealing with Jacob.

“Why won’t you defend yourself?” Jacob asked once, after scattering a group of bullies. “You could take any of them.”

Yeshua thought about it.

“I don’t know,” he said. “It just doesn’t feel right.”

Jacob shrugged. He didn’t need to understand a man to stand next to him.

Music came easily to him.

At eight, he arranged to trade dairy products from the family’s animals for harp lessons. By eleven, he was the best player in Nazareth, able to improvise melodies that made grown men stop their work to listen.

He loved the harp the way his father loved wood — not just the sound it made, but the logic of it. The mathematics of harmony. The way you could feel a song before you played it, sense where it wanted to go.

His mother would find him on the roof some evenings, playing softly to the stars, working out variations on old psalms. The music drew her even when his questions pushed her away.

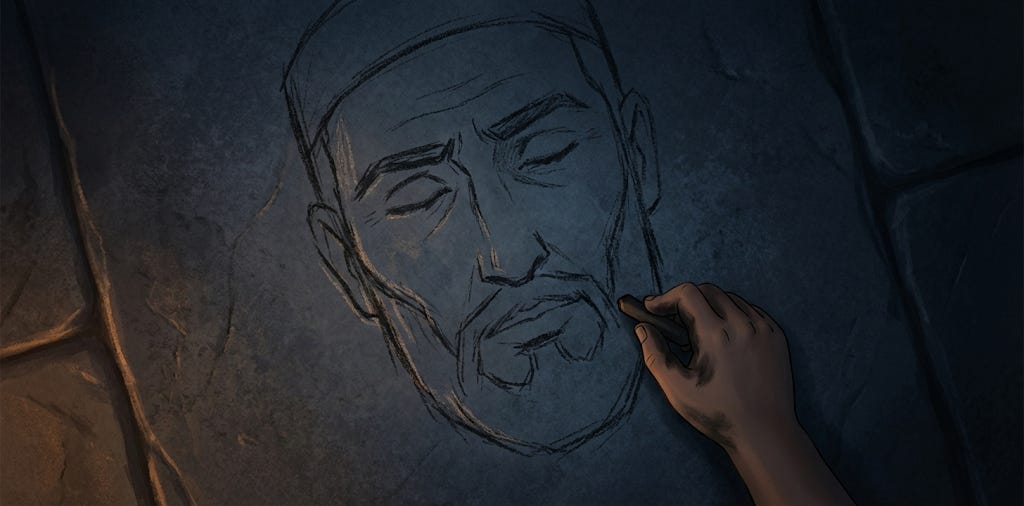

Drawing came just as naturally.

The problem started in his ninth year.

Yeshua had always sketched. Landscapes, animals, faces. He knew the law said you shouldn’t make images, but he couldn’t understand why a drawing of a flower was different from the flower itself. Both were beautiful. Both pointed toward the Creator. Why was one forbidden?

His parents knew. Joseph cared more about straight lines than strict law, and Mary had stopped trying to contain a mind she couldn’t keep up with.

But then he drew the chazan.

It happened during a slow afternoon at school. Yeshua was bored. He’d already memorized the passage they were studying, and his hand found a piece of charcoal and started moving on the stone floor. By the time anyone noticed, there was a remarkably accurate portrait of their teacher staring up at them.

The other students laughed. Then word spread. Then the elders came.

They arrived at Joseph’s workshop that evening, faces grim, voices sharp. This was not a small matter. The boy had violated the second commandment in the house of God. Something had to be done.

Joseph listened. Mary stood in the doorway with her arms folded.

Yeshua heard them from outside. After a while, he walked in.

“I’d like to speak,” he said.

The elders turned. One of them opened his mouth. Then he looked at the boy’s face and closed it.

“I drew a picture,” Yeshua said. “I don’t believe I did anything wrong. But I can see that it troubled you, and I don’t wish to cause trouble for my father.” He looked at Joseph. “I’ll do whatever you decide.”

The elders looked at each other. One of them sat down.

Joseph ruled that Yeshua must follow the rabbinical interpretation. No more pictures. No more drawings.

Yeshua nodded. Said nothing. Went to his room.

He still believed the drawing was good. He gave it up anyway. That cost him more than anyone knew.

He kept his word. He never drew again while Joseph was alive.

The year Yeshua turned eleven, Joseph took him to Scythopolis.

It was a business trip, materials for a construction project, but Joseph had another purpose. His son had been asking about the Greek cities for years, staring at them from the ridge, wondering what they were like inside. Joseph figured it was better to show him than to let his imagination run wild.

What Joseph didn’t expect was how much his son would love it.

Scythopolis was clean, orderly, beautiful. Marble buildings gleamed in the sun. The streets were laid out in perfect grids. There was an amphitheater. A massive open-air structure where the Greeks held games and performances.

The games were happening when they arrived. Athletic competitions. Displays of strength and speed. Young men from across the Decapolis competing for honor.

Yeshua was enthralled.

“Look at them,” he said. “The discipline. The training. The way they push their bodies to do more than seems possible.”

Joseph watched. He said nothing. His hand found the back of the boy’s neck and stayed there.

That evening, in their room at the inn, Yeshua made a suggestion.

“What if we built something like that in Nazareth? Not the pagan temples — just the athletic training. The boys there have nothing to do but get in trouble. If they had a place to run and compete—”

“My son.”

The tone stopped him cold. Joseph’s face had changed. His father was angry. Yeshua had never seen it before.

“Never again let me hear you give utterance to such an evil thought as long as you live.”

Yeshua stared. He’d never seen his father like this. The man who explained everything. Who answered every question. Who never raised his voice. That man was gone. What remained was stone.

“Very well, my father. It shall be so.”

He never mentioned Greek athletics again. Not as long as Joseph lived.

But he remembered.

That night, lying in the darkness of the inn, he turned the moment over in his mind. Not the words themselves — those were easy to accept. His father had forbidden something; he would obey.

It was the why that troubled him.

Joseph had given no reason. The man who always explained had explained nothing.

Why?

The games were discipline. Bodies trained like minds. Young men pushing through pain toward a standard they’d set for themselves. Yeshua had watched their faces. There was no sin in those faces. Only focus.

But Joseph had looked at the same athletes and seen an enemy.

Yeshua filed it. A question without an answer. He was collecting them now.

He was learning where his father’s map ended. Joseph’s wisdom covered most of the world. But there were territories beyond it. Places Yeshua could already see that his father could not. Someday he would have to walk into those territories alone.

For now, he would obey. He would be a good son. He would measure twice and cut once and follow the laws his father taught him.

But he would also remember. And he would keep asking questions, even the ones he couldn’t speak aloud.

“Very well, my father. It shall be so.”

That was what sons said. Yeshua lay still. His eyes open in the dark, fixed on nothing.

That same year, his brother Amos was born, and everything changed.

Mary’s pregnancy was difficult. The birth was worse. For weeks afterward, she was too ill to leave her bed. The younger children needed care. The household needed managing. Joseph was working longer hours to cover the medical expenses.

Yeshua stepped in.

He was eleven years old, and suddenly he was the one keeping the house standing. Cooking meals. Minding siblings. The music stopped. The questions stopped. The hours at the spring listening to travelers — gone.

He didn’t complain. The family needed him. He did what was in front of him.

He aged a decade in six months. The boy who climbed the ridge each Sabbath wondering about snow and sunlight was gone.

The chazan noticed. “You seem older,” he said one afternoon.

“I am older,” Yeshua replied. “Everyone gets older.”

“That’s not what I mean.”

“I know what you mean.”

Alone on the roof at night, he felt it.

A pressure behind his sternum. No words attached. No image. Just weight. The kind that comes before knowing, the way the air thickens before rain.

He’d tried to tell his father once. Joseph listened, asked a few questions, said very little.

He’d tried to tell his mother. Her face had cracked open, the hope and the fear fighting each other in real time. She asked so many questions he wished he’d never spoken.

So he stopped telling anyone. He let it grow in the dark.

It came strongest in the quiet hours. The house asleep. The stars overhead. His harp across his knees, not playing. Just sitting with it, the way you sit with someone who hasn’t spoken yet.

He was twelve now. Almost a man by Jewish reckoning. In a few months, he would go to Jerusalem for his first Passover, stand in the Temple, be counted among the sons of the commandment.

He didn’t know what would happen there. He knew it would matter.

The announcement came at dinner.

“Next spring,” Joseph said. “The Passover. We’re going to Jerusalem.”

Mary’s hand paused over the bread she was serving. They hadn’t been back since the flight. Since Bethlehem. Since everything.

“He’s almost thirteen,” Joseph continued. “The law requires it. It’s time.”

The younger children didn’t understand the weight of the moment. They chattered about the journey, the Temple, the crowds they’d heard about.

Yeshua said nothing. He watched his parents exchange a look — one of those silent conversations they’d been having his whole life. The ones that meant more than they would ever say to him.

He was going to Jerusalem. To the Temple. To the heart of everything his people believed.

The pressure behind his sternum tightened. He pressed his palm flat against it, as if holding something in place.

The caravan assembled in early April.

Over a hundred pilgrims from Nazareth and the surrounding villages, traveling together for safety. They would go east to avoid Samaria, follow the Jordan valley south, then climb to Jerusalem for the feast.

Yeshua walked with his father at first, asking questions about the route, the history of the places they passed. But as the days went on, he found himself moving ahead, scanning the horizon, impatient to see what came next.

Mary watched him from behind. This boy she had nursed and taught and protected. Walking ahead of her now, face turned toward something she could not see.

Her hand found her throat and stayed there.

Next week: Episode 4 — The Temple

Jesus is for everybody.

The Nazarene Saga tells the story of Jesus nobody showed you. If you’re new, start with Episode 1: Bethlehem and Episode 2: The Egypt Years.

New episodes every week. Pour something warm. Read slow.

Come back next week.

<3 EKO

P.S. Sometimes the classroom is the view

You might also love One Whale, a parable about what we carry.

This is inspiring… looking forward to the lost years in India. Appreciate your devotion and creativity. God bless.

I am so thankful for the commitment EKO has to this mission he is on.